|

http://singlepageappbook.com/goal.html

|

|

|||||||

|

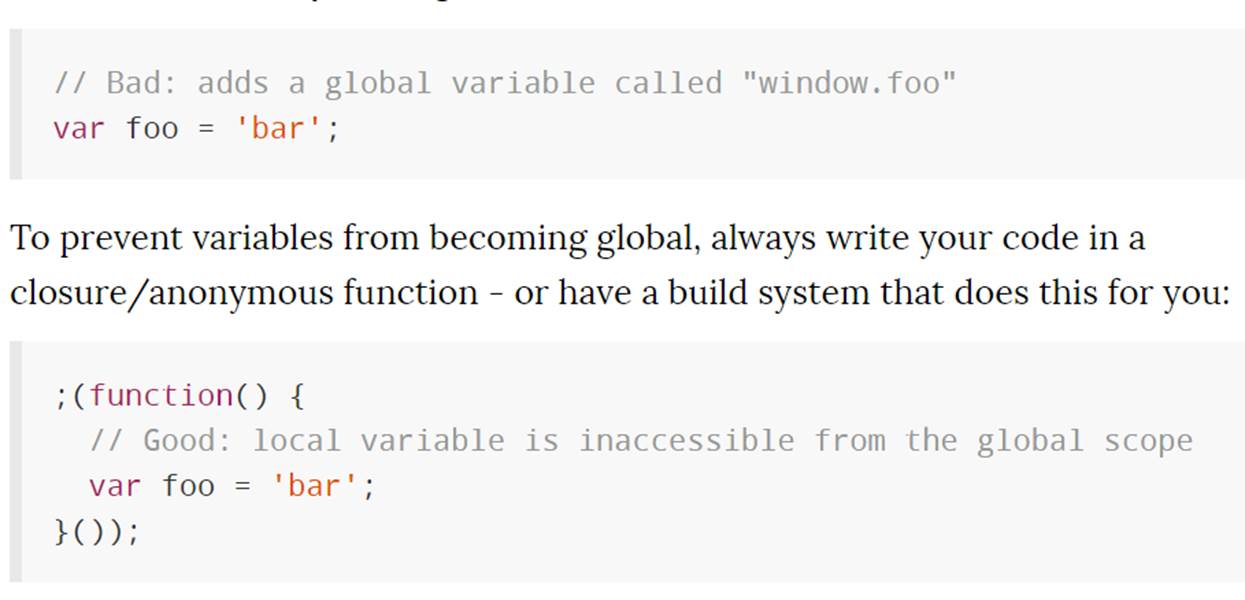

;(function() { // Bad: global names = global state window.FooMachine = {}; // Bad: implementation detail is made publicly accessible FooMachine.processBar = function () { ... }; FooMachine.doFoo = function(bar) { FooMachine.processBar(bar); // ... };

// Bad: exporting another object from the same file! // No logical mapping from modules to files. window.BarMachine = { ... }; })();

;(function() { // Good: the name is local to this module var FooMachine = {};

// Good: implementation detail is clearly local to the closure function processBar() { ... }

FooMachine.doFoo = function(bar) { processBar(bar); // ... };

// Good: only exporting the public interface, // internals can be refactored without worrying return FooMachine; })();

Do not leak global variables Do not expose implementation details Do not mix definition and instantiation/initialization Do not modify objects you don't own

Lexical Scope

Another point to mention is the lexical scope. Lexical scope means the children scope have the access to the variables defined in the parent scope.

|

||||||||

|

function checkScope() { var or let or none i = "func "; { let i = "block"; console.log(i); } console.log(i);

} checkScope();

block func

function checkScope() { var i = "func "; { var i = "block"; console.log(i); } console.log(i);

} checkScope();

block block

function checkScope() { let i = "func "; { var i = "block"; console.log(i); } console.log(i);

} checkScope();

Uncaught SyntaxError: Identifier 'i' has already been declared

function checkScope() { let or none i = "func "; { console.log(i); let i = "block"; console.log(i); } console.log(i);

} checkScope();

blockscope.htm:11 Uncaught ReferenceError: Cannot access 'i' before initialization

function checkScope() {

{

let i = "block"; console.log(i); } console.log(i);

}

blockscope.htm:15 Uncaught ReferenceError: i is not defined

function checkScope() {

{

Var or none i = "block"; console.log(i); } console.log(i);

} checkScope();

block block

function checkScope() { var or let or none i = "block"; { console.log(i); } console.log(i); } checkScope();

block block

|

|

|||||||

|

Create Strings using Template literals

const person = { name: 'saravan', } const greeting = `Hello ${person.name} what is your age?`

console.log(greeting)

Hello saravan what is your age?

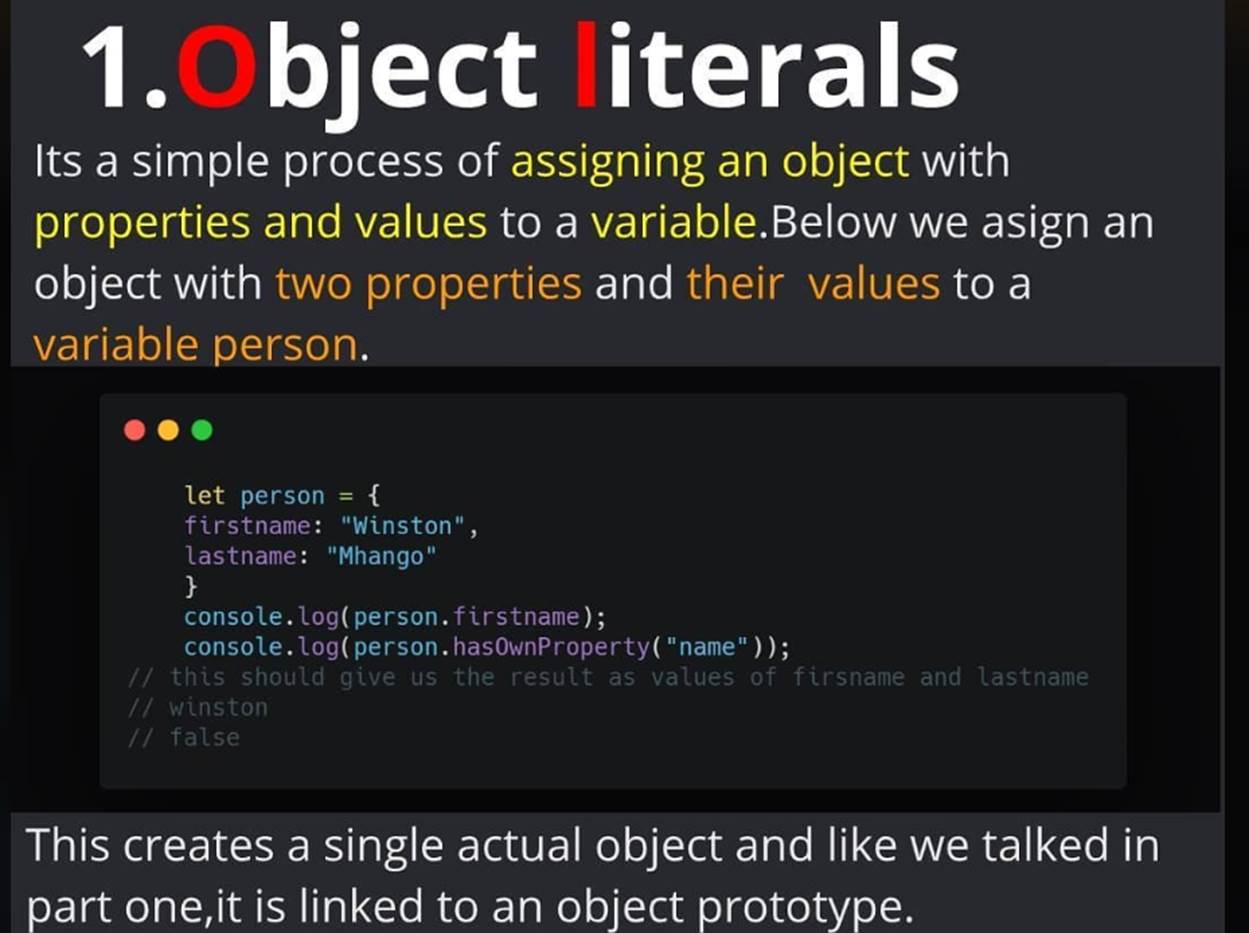

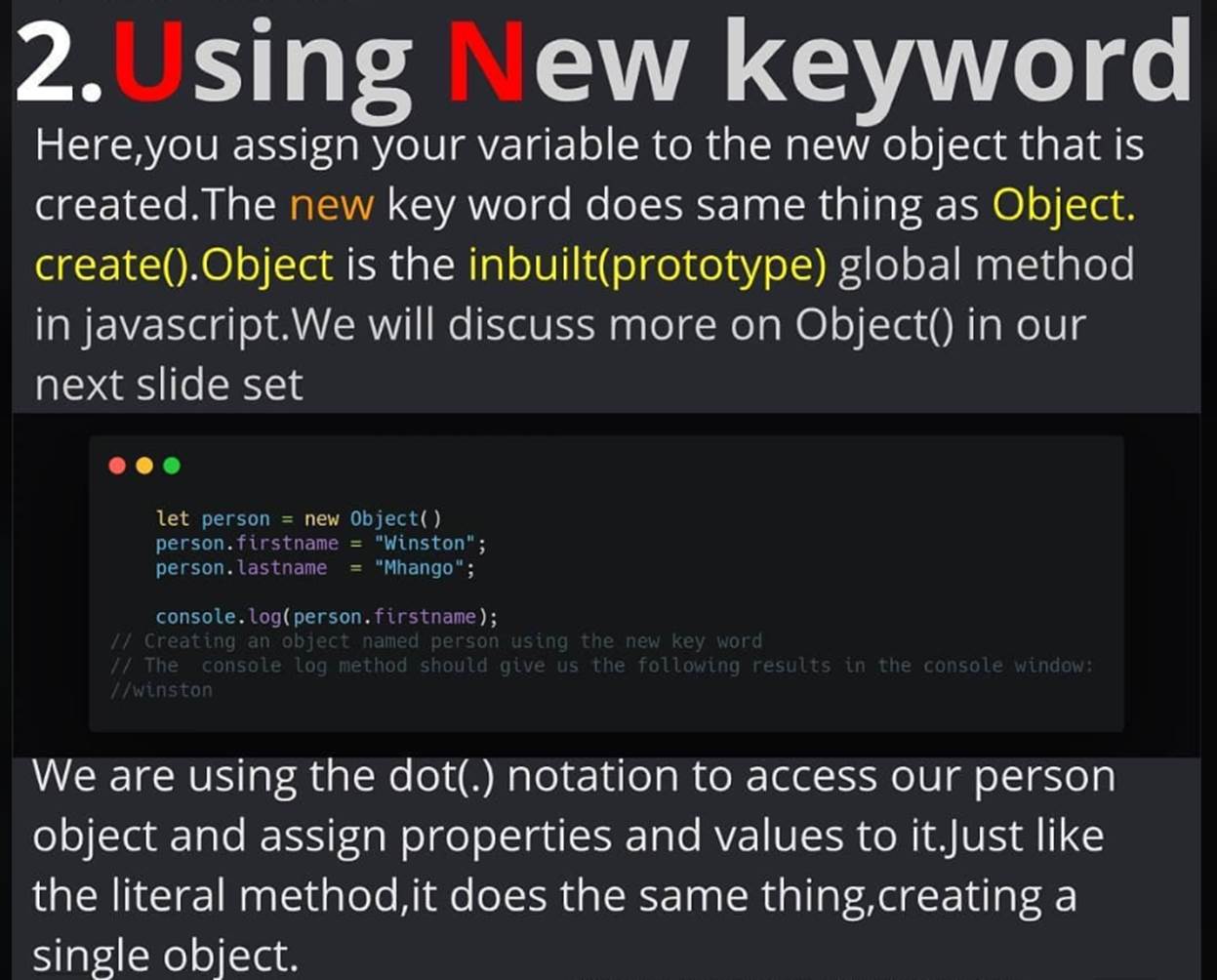

Object literals

const createPerson = (name) => { return {name: name} } console.log(createPerson("santhosh"));

or simply

const createPerson = (name) => { return {name} } console.log(createPerson("santhosh"));

const bicycle = { gear: 2, setGear : function (newGear) { this.gear = newGear; } }

bicycle.setGear(3) console.log(bicycle.gear)

or simply

const bicycle = { gear: 2, setGear (newGear) { this.gear = newGear; } }

bicycle.setGear(3) console.log(bicycle.gear)

var oldClass = function(myvar) { this.something = myvar }

var myobj = new oldClass('saravan')

console.log(myobj.something)

class newClass { constructor(myvar) { this.something = myvar } }

var myobj = new newClass('saravan') console.log(myobj.something)

function makeClass() { class newClass { constructor(myvar) { this.something = myvar } } return newClass }

const returnedClass = makeClass()

var myobj = new returnedClass('saravan') console.log(myobj.something)

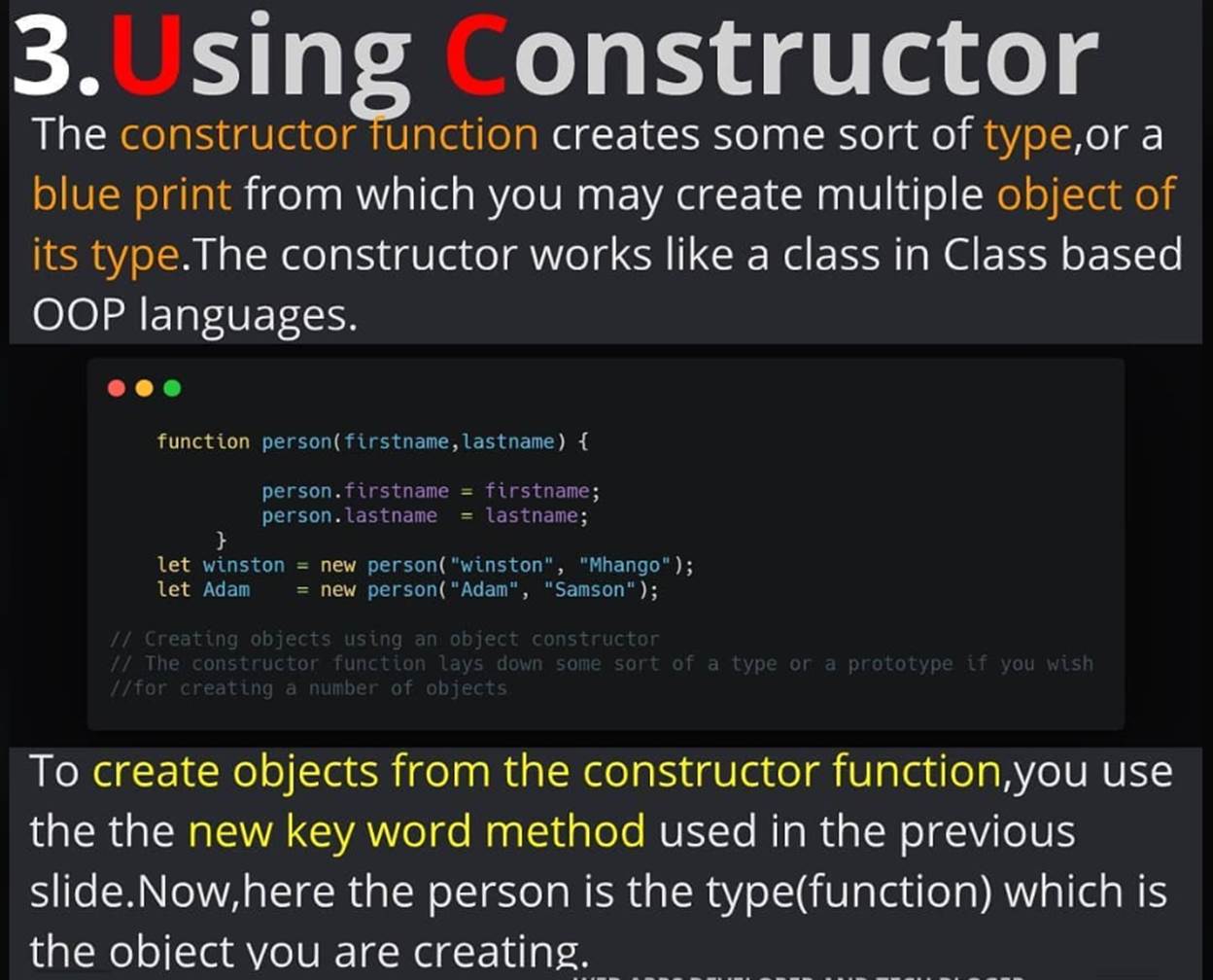

ConstructorPattern:

var peopleConstructor = function (name, age, state) { this.age = age this.name = name this.state = state

this.printPerson = function () { print(this.name + ', ' + this.age + ', ' + this.state) } }

// new is required var person1 = new peopleConstructor('john', 23, 'CA') var person2 = new peopleConstructor('kim', 27, 'SC')

person1.printPerson() person2.printPerson()

FactoryPattern:

var peopleFactory = function (name, age, state) { var temp = {} temp.age = age temp.name = name temp.state = state

temp.printPerson = function () { print(this.name + ', ' + this.age + ', ' + this.state) }

// new object will be created everytime. return that object return temp }

var person1 = peopleFactory('john', 23, 'CA') var person2 = peopleFactory('kim', 27, 'SC')

person1.printPerson() person2.printPerson()

PrototypePattern:

var peopleProto = function () {}

peopleProto.prototype.age = 0 peopleProto.prototype.name = 'no name' peopleProto.prototype.city = 'no city' peopleProto.prototype.printPerson = function () { print(this.name + ', ' + this.age + ', ' + this.state) }

var person1 = new peopleProto() //person1.name = 'john'; person1.age = 23 person1.city = 'CA' person1.printPerson() print('name' in person1) print(person1.hasOwnProperty('name'))

CreateFromObject:

var Pizza = { crust: 'then', toppings: 3, hasBacon: true, howmanyToppings: function () { return this.toppings }, }

var Pizza = function () { var crust = 'thin' var toppings = 3 this.hasBacon = true

this.getHasBacon = function () { return this.hasBacon }

this.getCrust = function () { return crust }

var getToppings = function () { return toppings }

var tmp = {} tmp.getToppings = getToppings return tmp }

var PizzaA = new Pizza() print(PizzaA.getToppings())

DynamicPrototypePattern:

var peopleDynamicProto = function (name, age, state) { this.age = age this.name = name this.state = state

this.printPerson = function () { print(this.name + ', ' + this.age + ', ' + this.state) }

if (typeof this.printPerson !== 'function') { peopleDynamicProto.prototype.printPerson = function () { print(this.name + ', ' + this.age + ', ' + this.state) } } }

var person1 = new peopleDynamicProto('john', 23, 'CA') person1.printPerson()

|

||||||

|

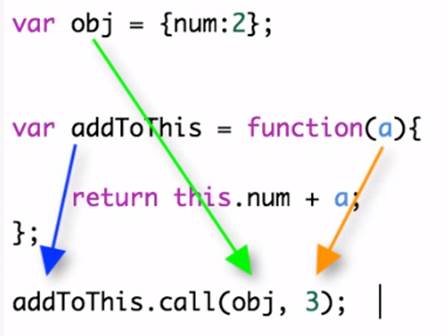

var obj = { num: 2 };

var addToThis = function (a) { return this.num + a; };

print(addToThis.call(obj, 3));

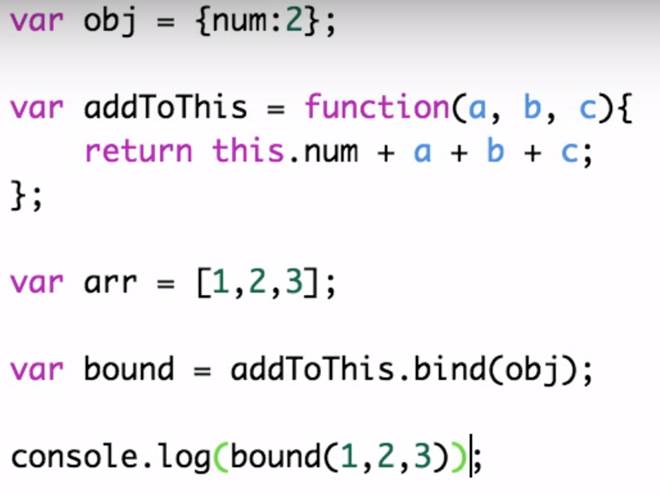

var addToThis = function (a, b, c) { return this.num + a + b + c; };

print(addToThis.call(obj, 1, 2, 3));

var obj2 = { num: 5 };

var arr = [1, 2, 3];

print(addToThis.apply(obj, arr)); print(addToThis.apply(obj2, arr));

var bound = addToThis.bind(obj);

console.dir(bound);

print(bound(1, 2, 3));

|

||||||

|

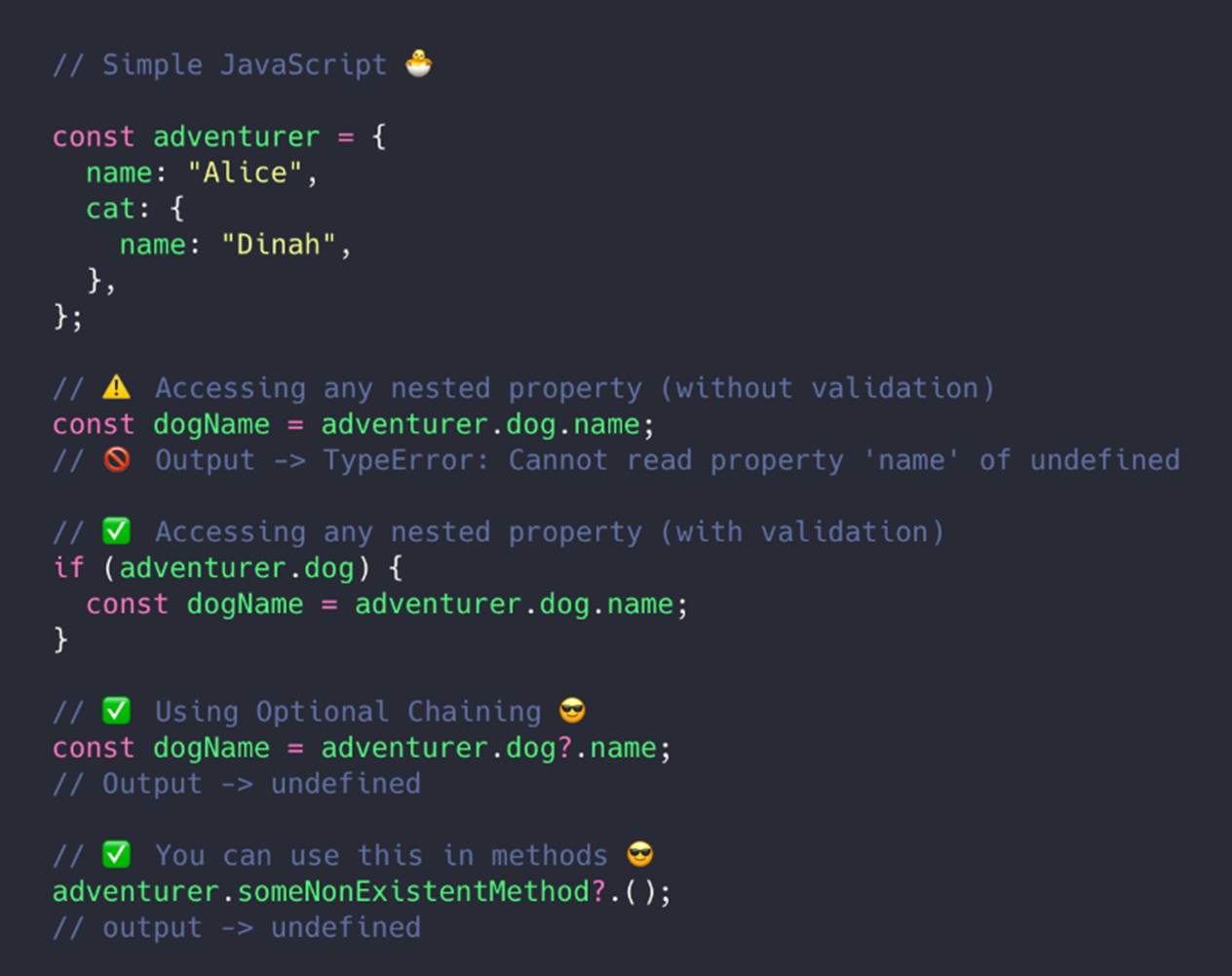

Object properties can be accessed by using the dot notation or the bracket notation:

const myObj = { foo: 'bar', age: 42 }myObj.foo // 'bar' accessed through dot notation myObj['age'] // 42 accessed through bracket notation

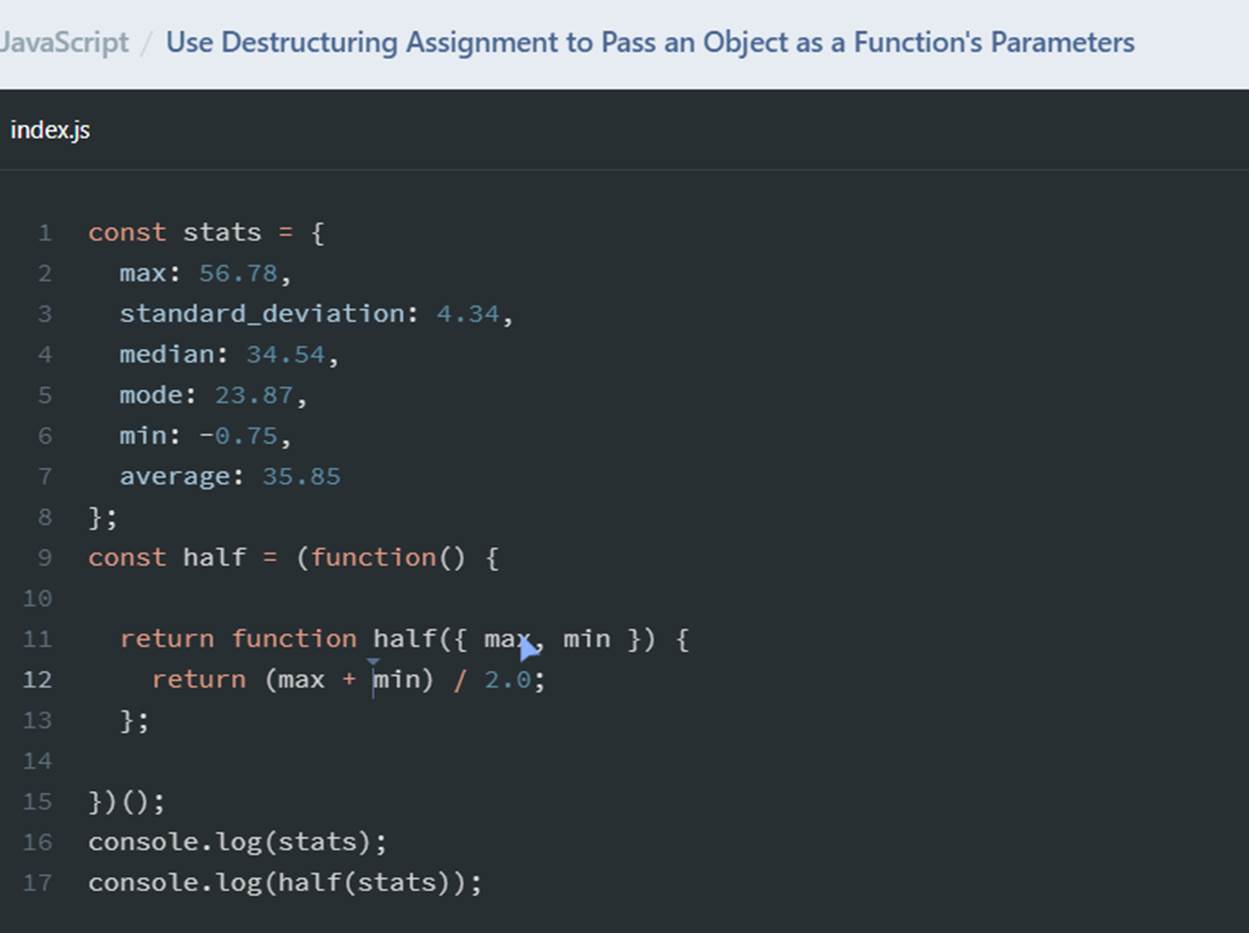

The object destructuring assignment syntax gives us a third way to access object properties:

const { foo } = myObj // 'bar' const { age } = myObj // 42// or all in one line:const { foo, age } = myObj // foo === 'bar', age === 42

getPropValue

export const getPropValue = (obj, key) => key.split('.').reduce((o, x) => o == undefined ? o : o[x] , obj)

(Note that the double equals ==checks for both undefined and null ) We could pass in a key of the form prop.nestedprop.nestedprop and it would happily return the value for that nested property. For example, if the object were: const obj = { main: { content: { title: 'old pier', description: 'seagulls paradise' } } }

we could retrieve the title as:

const title = getPropValue(obj, 'main.content.title') // 'old pier'

obj || {}

const obj = { main: 'Brighton seagull' } const { main } = obj || {} // 'Brighton seagull'

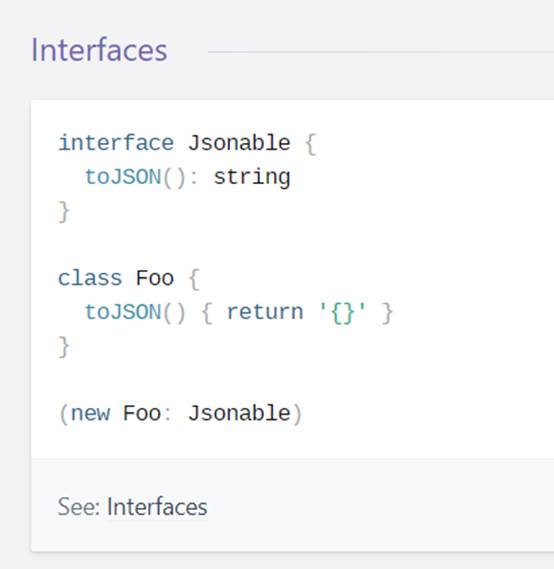

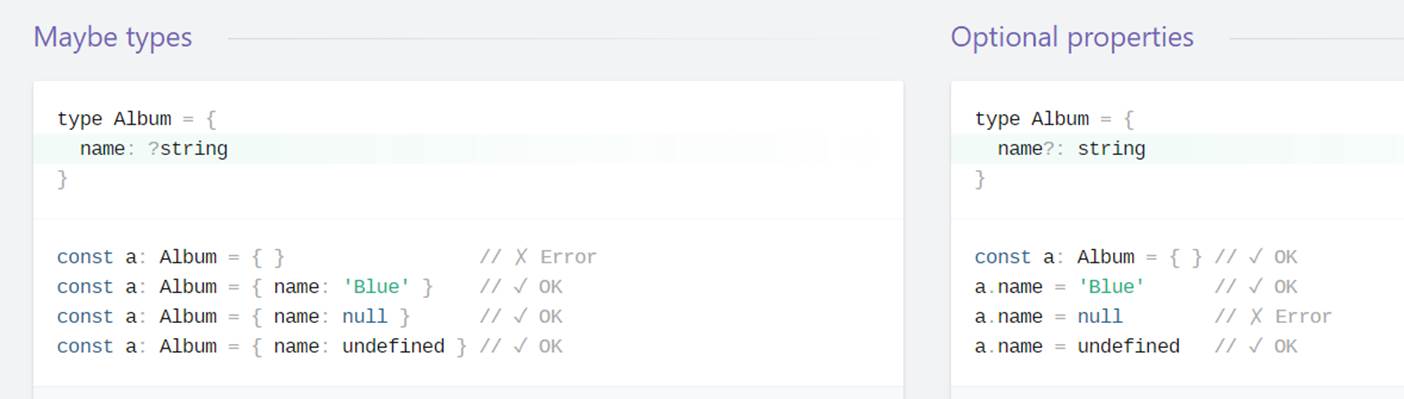

https://devhints.io/flow

|

|

https://www.sitepoint.com/use-jquerys-ajax-function/

jQuery’s most-used Ajax shorthand methods: $.get(), $.post(), and $.load()

$('#main-menu a').on('click', function(event) { event.preventDefault();

$('#main').load(this.href + ' #main *', function(responseText, status) { if (status === 'success') { $('#notification-bar').text('The page has been successfully loaded'); } else { $('#notification-bar').text('An error occurred'); } }); });

Updating this snippet to employ the $.ajax() function, we obtain the code shown below:

$('#main-menu a').on('click', function(event) { event.preventDefault();

$.ajax(this.href, { success: function(data) { $('#main').html($(data).find('#main *')); $('#notification-bar').text('The page has been successfully loaded'); }, error: function() { $('#notification-bar').text('An error occurred'); } }); });

The code to achieve this goal is as follows:

$.ajax({ url: 'http://api.joind.in/v2.1/talks/10889', data: { format: 'json' }, error: function() { $('#info').html('<p>An error has occurred</p>'); }, dataType: 'jsonp', success: function(data) { var $title = $('<h1>').text(data.talks[0].talk_title); var $description = $('<p>').text(data.talks[0].talk_description); $('#info') .append($title) .append($description); }, type: 'GET' });

|

|

https://www.toptal.com/javascript/functional-programming-javascript

Pure vs. Impure Functions Pure functions take some input and give a fixed output. Also, they cause no side effects in the outside world.

const add = (a, b) => a + b;

Here, add is a pure function. This is because, for a fixed value of a and b, the output will always be the same.

const SECRET = 42; const getId = (a) => SECRET * a;

getId is not a pure function. The reason being that it uses the global variable SECRET for computing the output. If SECRET were to change, the getId function will return a different value for the same input. Thus, it is not a pure function.

Creating Your Own Pure Function We can create our pure function as well. Let’s do one for duplicating a string n number of times.

const duplicate = (str, n) => n < 1 ? '' : str + duplicate(str, n-1); This function duplicates a string n times and returns a new string. duplicate('hooray!', 3) // hooray!hooray!hooray!

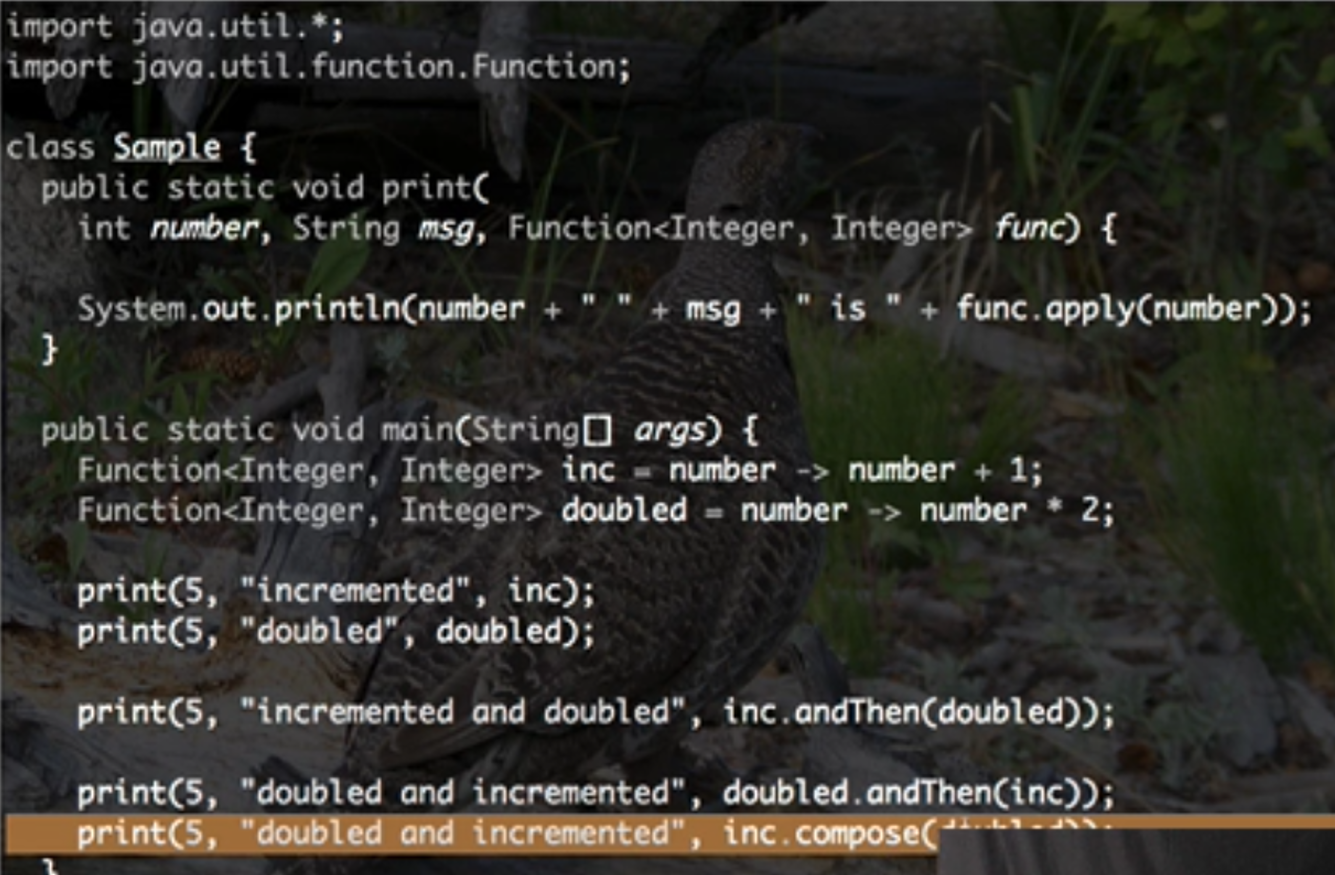

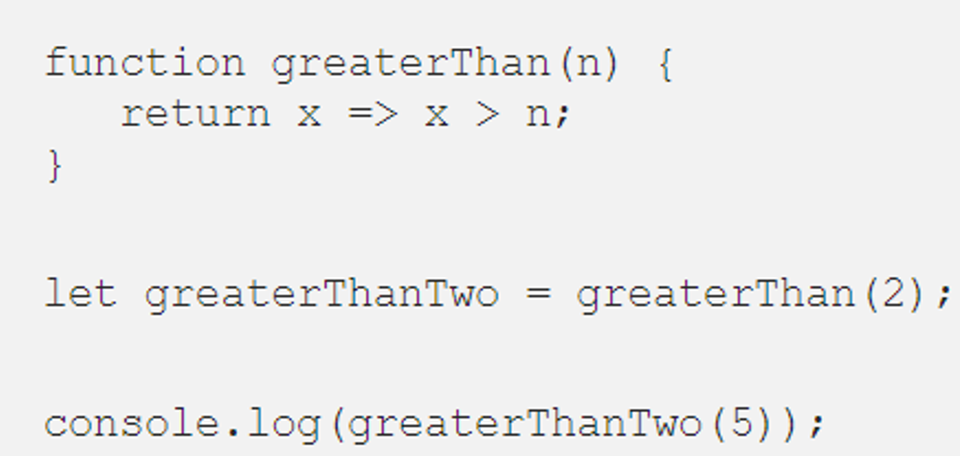

Higher-order Functions Higher-order functions are functions that accept a function as an argument and return a function. Often, they are used to add to the functionality of a function.

const withLog = (fn) => { return (...args) => { console.log(`calling ${fn.name}`); return fn(...args); }; };

In the above example, we create a withLog higher-order function that takes a function and returns a function that logs a message before the wrapped function runs.

const add = (a, b) => a + b; const addWithLogging = withLog(add); addWithLogging(3, 4); // calling add // 7

withLog HOF can be used with other functions as well and it works without any conflicts or writing extra code. This is the beauty of a HOF.

const addWithLogging = withLog(add); const hype = s => s + '!!!'; const hypeWithLogging = withLog(hype); hypeWithLogging('Sale'); // calling hype // Sale!!! One can also call it without defining a combining function. withLog(hype)('Sale'); // calling hype // Sale!!!

Currying Currying means breaking down a function that takes multiple arguments into one or multiple levels of higher-order functions.

Let’s take the add function.

const add = (a, b) => a + b;

When we are to curry it, we rewrite it distributing arguments into multiple levels as follows.

const add = a => { return b => { return a + b; }; }; add(3)(4); // 7

The benefit of currying is memoization. We can now memoize certain arguments in a function call so that they can be reused later without duplication and re-computation.

// assume getOffsetNumer() call is expensive const addOffset = add(getOffsetNumber()); addOffset(4); // 4 + getOffsetNumber() addOffset(6);

This is certainly better than using both arguments everywhere.

// (X) DON"T DO THIS add(4, getOffsetNumber()); add(6, getOffsetNumber()); add(10, getOffsetNumber());

We can also reformat our curried function to look succinct. This is because each level of the currying function call is a single line return statement. Therefore, we can use arrow functions in ES6 to refactor it as follows.

const add = a => b => a + b;

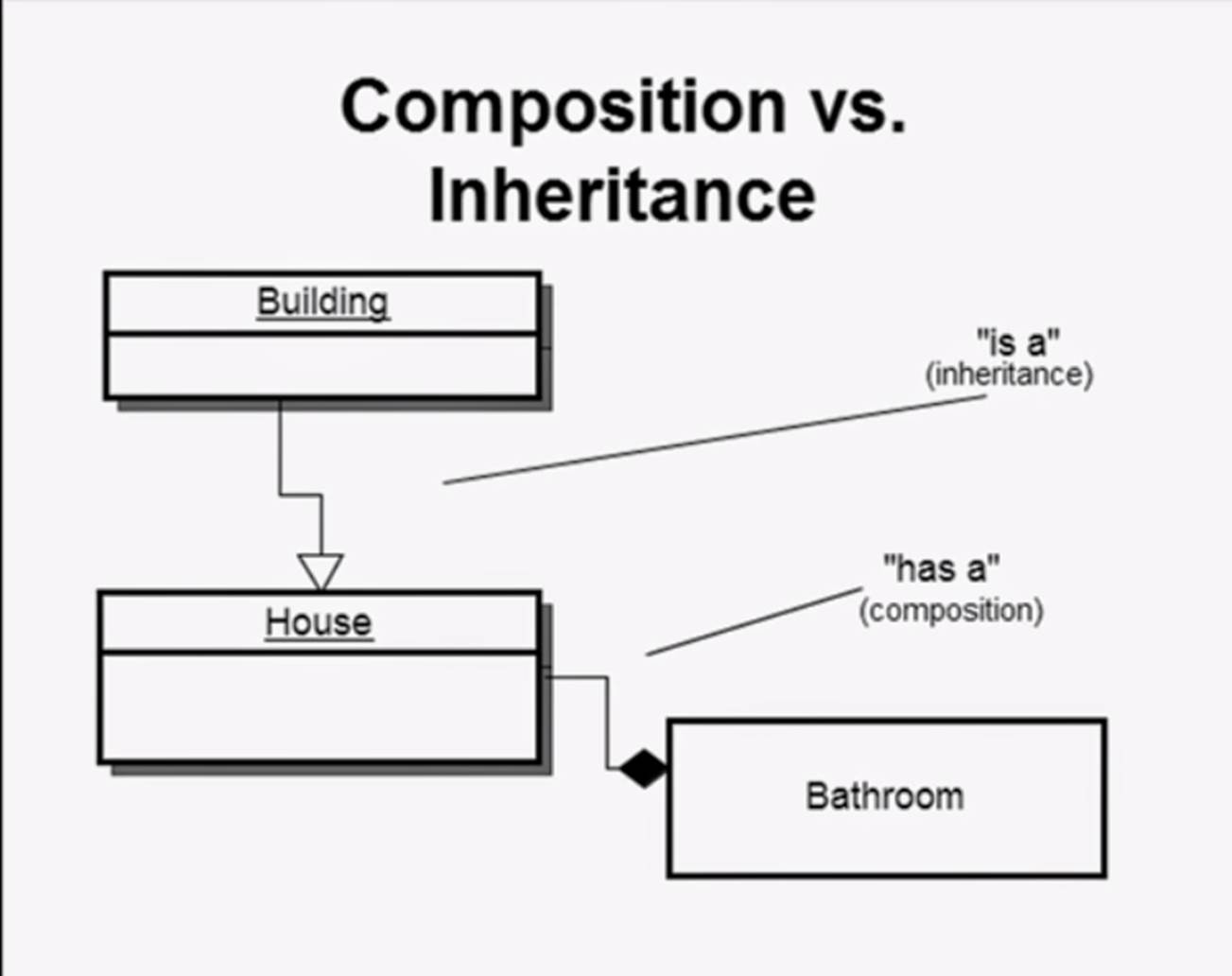

Composition

In mathematics, composition is defined as passing the output of one function into input of another so as to create a combined output. The same is possible in functional programming since we are using pure functions.

To show an example, let’s create some functions. The first function is range, which takes a starting number a and an ending number b and creates an array consisting of numbers from a to b.

const range = (a, b) => a > b ? [] : [a, ...range(a+1, b)];

Then we have a function multiply that takes an array and multiplies all the numbers in it.

const multiply = arr => arr.reduce((p, a) => p * a);

We will use these functions together to calculate factorial.

const factorial = n => multiply(range(1, n)); factorial(5); // 120 factorial(6); // 720

The above function for calculating factorial is similar to f(x) = g(h(x)), thus demonstrating the composition property.

Higher-Order Functions A higher-order function is a function that gets a function as an argument. It may or may not return a function as its resulting output. Here’s an example of Higher-Order Function:

|

|

Function Composition

Functional Programming won’t be completely functional without this feature. Function Composition is an act of composing/creating functions that allow you to further simplify and compress your functions by taking functions as an argument and return an output. It may also return another function as its output other than numerical/string values. Here is an example of Function Composition:

var compose = (f, g) => (x) => f(g(x));

let list = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]; let accumulator = 0;

function sum(list, accumulator) { if (list.length == 0) { return accumulator; }

return sum(list.slice(1), accumulator + list[0]); }

sum(list, accumulator); // 15 list; // [1, 2, 3, 4, 5] accumulator; // 0

|

|

SPLICE

let arr = ["I", "study", "JavaScript"];

arr.splice(1, 1); // from index 1 remove 1 element

alert( arr ); // ["I", "JavaScript"]

let arr = ["I", "study", "JavaScript", "right", "now"];

// remove 3 first elements and replace them with another arr.splice(0, 3, "Let's", "dance");

alert( arr ) // now ["Let's", "dance", "right", "now"]

let arr = ["I", "study", "JavaScript", "right", "now"];

// remove 2 first elements let removed = arr.splice(0, 2);

alert( removed ); // "I", "study" <-- array of removed elements

let arr = ["I", "study", "JavaScript"];

// from index 2 // delete 0 // then insert "complex" and "language" arr.splice(2, 0, "complex", "language");

alert( arr ); // "I", "study", "complex", "language", "JavaScript"

let arr = [1, 2, 5];

// from index -1 (one step from the end) // delete 0 elements, // then insert 3 and 4 arr.splice(-1, 0, 3, 4);

alert( arr ); // 1,2,3,4,5

SLICE

let arr = ["t", "e", "s", "t"];

alert( arr.slice(1, 3) ); // e,s (copy from 1 to 3)

alert( arr.slice(-2) ); // s,t (copy from -2 till the end)

let arr = [1, 2];

// create an array from: arr and [3,4] alert( arr.concat([3, 4]) ); // 1,2,3,4

// create an array from: arr and [3,4] and [5,6] alert( arr.concat([3, 4], [5, 6]) ); // 1,2,3,4,5,6

// create an array from: arr and [3,4], then add values 5 and 6 alert( arr.concat([3, 4], 5, 6) ); // 1,2,3,4,5,6

let arr = [1, 2];

let arrayLike = { 0: "something", 1: "else", [Symbol.isConcatSpreadable]: true, length: 2 };

alert( arr.concat(arrayLike) ); // 1,2,something,else

let countries = ['Österreich', 'Andorra', 'Vietnam'];

alert( countries.sort( (a, b) => a > b ? 1 : -1) ); // Andorra, Vietnam, Österreich (wrong) ["Bilbo", "Gandalf", "Nazgul"].forEach(alert);

["Bilbo", "Gandalf", "Nazgul"].forEach((item, index, array) => { alert(`${item} is at index ${index} in ${array}`); });

let result = arr.find(function(item, index, array) { // if true is returned, item is returned and iteration is stopped // for falsy scenario returns undefined });

let users = [ {id: 1, name: "John"}, {id: 2, name: "Pete"}, {id: 3, name: "Mary"} ];

let user = users.find(item => item.id == 1);

alert(user.name); // John

let users = [ {id: 1, name: "John"}, {id: 2, name: "Pete"}, {id: 3, name: "Mary"} ];

// returns array of the first two users let someUsers = users.filter(item => item.id < 3);

alert(someUsers.length); // 2

let lengths = ["Bilbo", "Gandalf", "Nazgul"].map(item => item.length); alert(lengths); // 5,7,6

let arr = [ 1, 2, 15 ];

// the method reorders the content of arr arr.sort();

alert( arr ); // 1, 15, 2

function compareNumeric(a, b) { if (a > b) return 1; if (a == b) return 0; if (a < b) return -1; }

let arr = [ 1, 2, 15 ];

arr.sort(compareNumeric);

alert(arr); // 1, 2, 15

arr.sort( (a, b) => a - b );

let countries = ['Österreich', 'Andorra', 'Vietnam'];

alert( countries.sort( (a, b) => a > b ? 1 : -1) ); // Andorra, Vietnam, Österreich (wrong)

let arr = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]; arr.reverse();

alert( arr ); // 5,4,3,2,1

let names = 'Bilbo, Gandalf, Nazgul';

let arr = names.split(', ');

for (let name of arr) { alert( `A message to ${name}.` ); }

let arr = 'Bilbo, Gandalf, Nazgul, Saruman'.split(', ', 2);

alert(arr); // Bilbo, Gandalf

let str = "test";

alert( str.split('') ); // t,e,s,t let arr = ['Bilbo', 'Gandalf', 'Nazgul'];

let str = arr.join(';'); // glue the array into a string using ;

alert( str ); // Bilbo;Gandalf;Nazgul

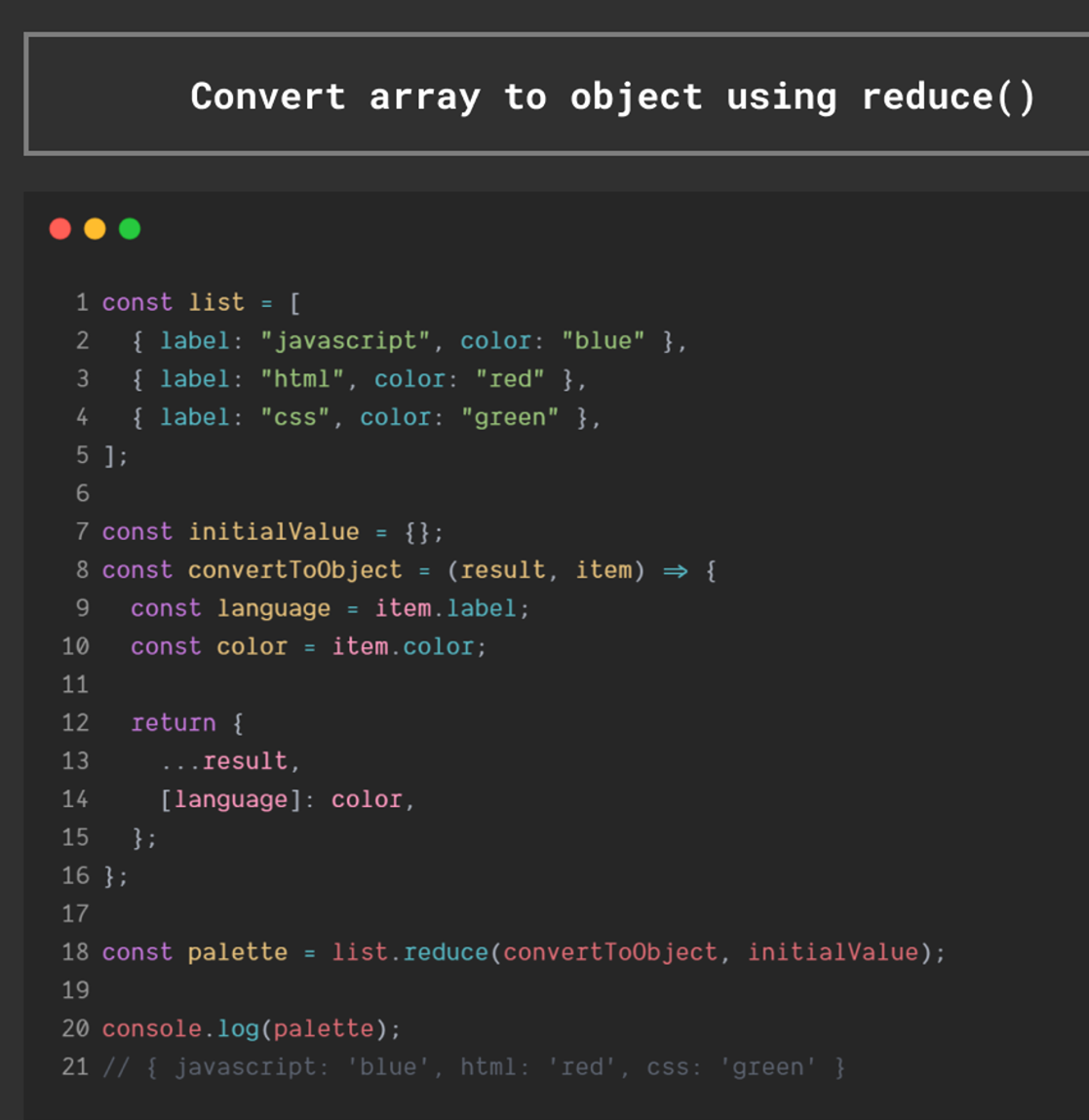

let value = arr.reduce(function(accumulator, item, index, array) { // ... }, [initial]);

let arr = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

let result = arr.reduce((sum, current) => sum + current, 0);

alert(result); // 15

let arr = [];

// Error: Reduce of empty array with no initial value // if the initial value existed, reduce would return it for the empty arr. arr.reduce((sum, current) => sum + current);

let army = { minAge: 18, maxAge: 27, canJoin(user) { return user.age >= this.minAge && user.age < this.maxAge; } };

let users = [ {age: 16}, {age: 20}, {age: 23}, {age: 30} ];

// find users, for who army.canJoin returns true let soldiers = users.filter(army.canJoin, army);

alert(soldiers.length); // 2 alert(soldiers[0].age); // 20 alert(soldiers[1].age); // 23

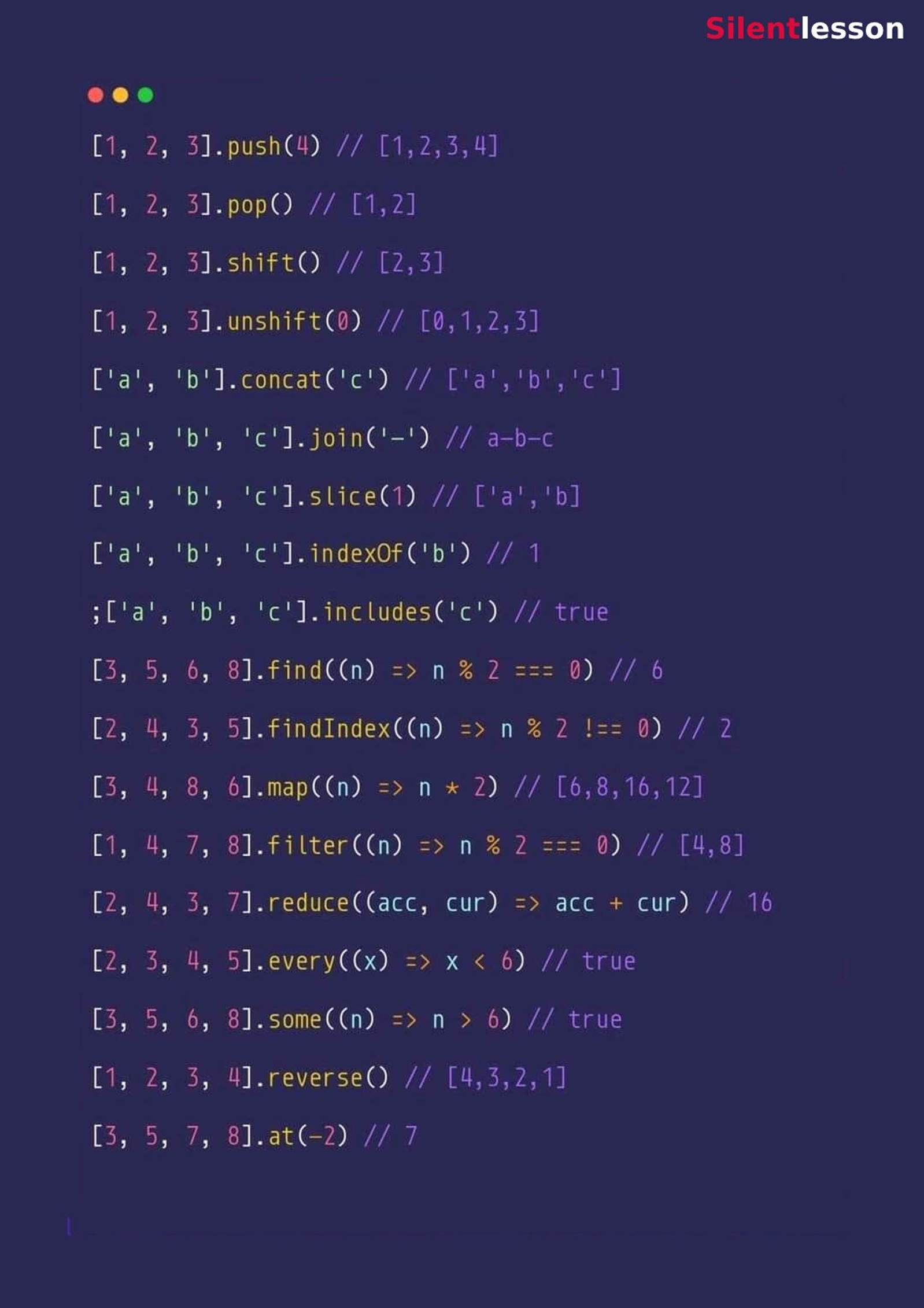

A cheat sheet of array methods:

|

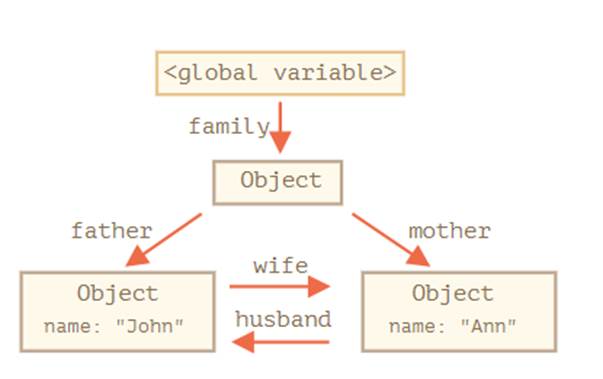

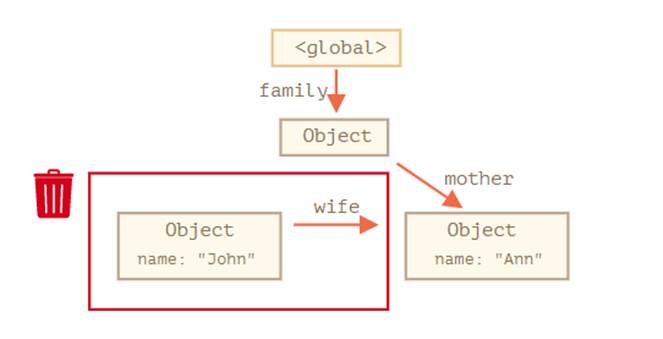

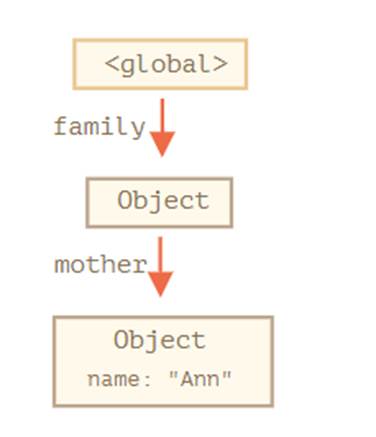

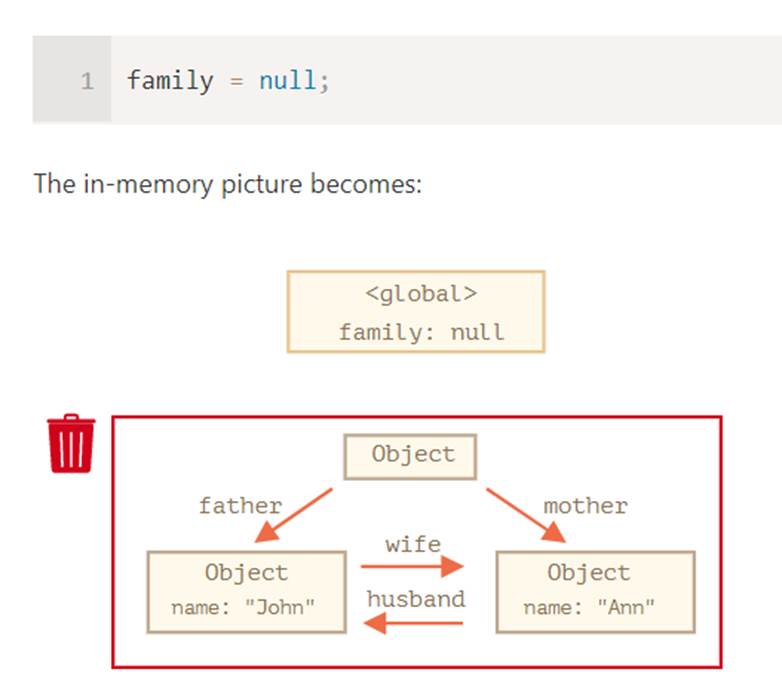

Function The resulting memory structure:

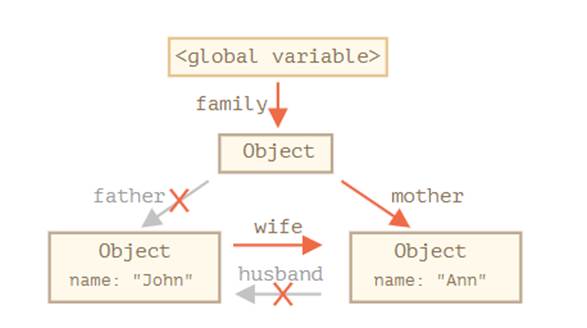

As of now, all objects are reachable. Now let’s remove two references:

It’s not enough to delete only one of these two references, because all objects would still be reachable. But if we delete both, then we can see that John has no incoming reference any more:

Outgoing references do not matter. Only incoming ones can make an object reachable. So, John is now unreachable and will be removed from the memory with all its data that also became unaccessible. After garbage collection:

let user = { name: "John", age: 30,

sayHi() { alert( user.name ); // leads to an error }

};

let admin = user; user = null; // overwrite to make things obvious

admin.sayHi(); // Whoops! inside sayHi(), the old name is used! error!

let user = { name: "John" }; let admin = { name: "Admin" };

function sayHi() { alert( this.name ); }

// use the same function in two objects user.f = sayHi; admin.f = sayHi;

// these calls have different this // "this" inside the function is the object "before the dot" user.f(); // John (this == user) admin.f(); // Admin (this == admin)

admin['f'](); // Admin (dot or square brackets access the method – doesn't matter)

Arrow functions are special: they don’t have their “own” this. If we reference this from such a function, it’s taken from the outer “normal” function. For instance, here arrow() uses this from the outer user.sayHi() method:

let user = { firstName: "Ilya", sayHi() { let arrow = () => alert(this.firstName); arrow(); } };

user.sayHi(); // Ilya

function makeUser() { return { name: "John", ref: this }; };

let user = makeUser();

alert( user.ref.name ); // Error: Cannot read property 'name' of undefined

function makeUser() { return { name: "John", ref() { return this; } }; };

let user = makeUser();

alert( user.ref().name ); // John

There’s a ladder object that allows to go up and down:

let ladder = { step: 0, up() { this.step++; return this; }, down() { this.step--; return this; }, showStep() { alert( this.step ); return this; } }

Now, if we need to make several calls in sequence, can do it like this:

ladder.up(); ladder.up(); ladder.down(); ladder.showStep(); // 1 ladder.up().up().down().showStep(); // 1

Modify the code of up, down and showStep to make the calls chainable, like this:

function User(name) { this.name = name; this.isAdmin = false; }

let user = new User("Jack");

When a function is executed with new, it does the following steps:

function User(name) { // this = {}; (implicitly)

// add properties to this this.name = name; this.isAdmin = false;

// return this; (implicitly) }

function User() { this.name = ‘saravan’ }

// without "new": User(); // not possible without new

// with "new": new User();

Now you can do without new

function User(name) { if (!new.target) { // if you run me without new return new User(name); // ...I will add new for you }

this.name = name; }

let john = User("John"); // redirects call to new User

function BigUser() {

this.name = "John";

return { name: "Godzilla" }; // <-- returns this object }

new BigUser().name

By the way, we can omit parentheses after new, if it has no arguments:

let user = new User; // <-- no parentheses // same as let user = new User();

function User(name) { this.name = name;

this.sayHi = function() { console.log( "My name is: " + this.name ); }; }

function User(name) { name,

sayHi = () { console.log( "My name is: " + this.name ); }; }

const User = { name : '', sayHi : function () { console.log('Hi') } }

const User2 = { name : '', sayHi : () => { console.log('Hi') } }

let user = { name: "John" };

let permissions1 = { canView: true }; let permissions2 = { canEdit: true };

// copies all properties from permissions1 and permissions2 into user Object.assign(user, permissions1, permissions2);

// now user = { name: "John", canView: true, canEdit: true }

If the copied property name already exists, it gets overwritten:

let user = { name: "John" };

Object.assign(user, { name: "Pete" });

alert(user.name); // now user = { name: "Pete" }

We also can use Object.assign to replace for..in loop for simple cloning:

let user = { name: "John", age: 30 };

let clone = Object.assign({}, user);

DANGER

let user = { name: "John", sizes: { height: 182, width: 50 } };

let clone = Object.assign({}, user);

alert( user.sizes === clone.sizes ); // true, same object

// user and clone share sizes user.sizes.width++; // change a property from one place alert(clone.sizes.width); // 51, see the result from the other one

let john = { name: "John" };

// the object can be accessed, john is the reference to it

// overwrite the reference john = null;

// the object will be removed from memory

let john = { name: "John" };

let array = [ john ];

john = null; // overwrite the reference

// john is stored inside the array, so it won't be garbage-collected // we can get it as array[0]

let john = { name: "John" };

let map = new Map(); map.set(john, "...");

john = null; // overwrite the reference

// john is stored inside the map, // we can get it by using map.keys()

let weakMap = new WeakMap();

let obj = {};

weakMap.set(obj, "ok"); // works fine (object key)

// can't use a string as the key weakMap.set("test", "Whoops"); // Error, because "test" is not an object

let john = { name: "John" };

let weakMap = new WeakMap(); weakMap.set(john, "...");

john = null; // overwrite the reference

// john is removed from memory!

// 📁 visitsCount.js let visitsCountMap = new Map(); // map: user => visits count

// increase the visits count function countUser(user) { let count = visitsCountMap.get(user) || 0; visitsCountMap.set(user, count + 1); }

// 📁 main.js let john = { name: "John" };

countUser(john); // count his visits

// later john leaves us john = null;

Now john object should be garbage collected, but remains in memory, as it’s a key in visitsCountMap.

We need to clean visitsCountMap when we remove users, otherwise it will grow in memory indefinitely. Such cleaning can become a tedious task in complex architectures. We can avoid it by switching to WeakMap instead:

// 📁 visitsCount.js let visitsCountMap = new WeakMap(); // weakmap: user => visits count

// increase the visits count function countUser(user) { let count = visitsCountMap.get(user) || 0; visitsCountMap.set(user, count + 1); }

// 📁 cache.js let cache = new Map();

// calculate and remember the result function process(obj) { if (!cache.has(obj)) { let result = /* calculations of the result for */ obj;

cache.set(obj, result); }

return cache.get(obj); }

// Now we use process() in another file:

// 📁 main.js let obj = {/* let's say we have an object */};

let result1 = process(obj); // calculated

// ...later, from another place of the code... let result2 = process(obj); // remembered result taken from cache

// ...later, when the object is not needed any more: obj = null;

alert(cache.size); // 1 (Ouch! The object is still in cache, taking memory!)

or multiple calls of process(obj) with the same object, it only calculates the result the first time, and then just takes it from cache. The downside is that we need to clean cache when the object is not needed any more. If we replace Map with WeakMap, then this problem disappears: the cached result will be removed from memory automatically after the object gets garbage collected.

let visitedSet = new WeakSet();

let john = { name: "John" }; let pete = { name: "Pete" }; let mary = { name: "Mary" };

visitedSet.add(john); // John visited us visitedSet.add(pete); // Then Pete visitedSet.add(john); // John again

// visitedSet has 2 users now

// check if John visited? alert(visitedSet.has(john)); // true

// check if Mary visited? alert(visitedSet.has(mary)); // false

john = null;

// visitedSet will be cleaned automatically

The most notable limitation of WeakMap and WeakSet is the absence of iterations, and inability to get all current content.

// the symbolic property is only known to our code let isRead = Symbol("isRead"); messages[0][isRead] = true;

Now third-party code probably won’t see our extra property.

|

|

Return Response From Asynchronous Call Using jQuery AJAX

$(function(){ $('#btnjQueryAjax').click(function(){ $.ajax({ url : 'http://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/users', type: 'GET', success: function(response) { $('#divResult').html(JSON.stringify(response)) }, error : function(error) { console.log('error is ', error) } }) }) })

/* helper.js */

const helper = (function(){ function getPhotos(){ return fetch('https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/photos') .then((response) => { return response.json() }) } function getPosts(){ return fetch('https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/posts') .then((response) => { return response.json() }) } return { getPhotos, getPosts } })();

/* app.js */

helper.getPhotos() .then(function(response){ console.log(response); return helper.getPosts() }) .then(function(response){ console.log(response); }) .catch(function(error){ console.log(`Error occured ${error}`); })

async function callAPI(){ let photos = helper.getPhotos(); let posts = helper.getPosts(); let [photosResponse, postsResponse] = [await photos, await posts]; console.log(photosResponse, postsResponse) } callAPI();

|

|

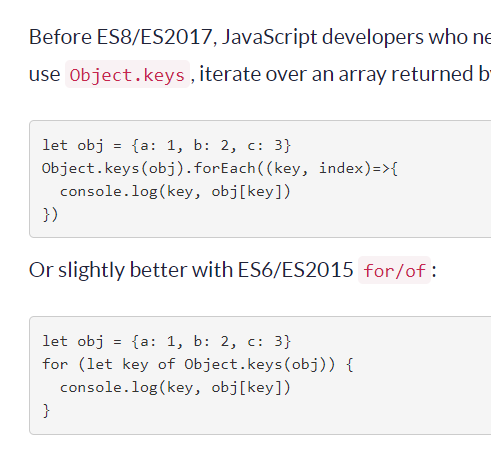

function convertToRoman(num) { var roman = { M: 1000, CM: 900, D: 500, CD: 400, C: 100, XC: 90, L: 50, XL: 40, X: 10, IX: 9, V: 5, IV: 4, I: 1 }; var str = '';

for (var i of Object.keys(roman)) { var q = Math.floor(num / roman[i]); num -= q * roman[i]; str += i.repeat(q); }

return str; }

var romanMatrix = [ [1000, 'M'], [900, 'CM'], [500, 'D'], [400, 'CD'], [100, 'C'], [90, 'XC'], [50, 'L'], [40, 'XL'], [10, 'X'], [9, 'IX'], [5, 'V'], [4, 'IV'], [1, 'I'] ];

function convertToRoman(num) { if (num === 0) { return ''; } for (var i = 0; i < romanMatrix.length; i++) { if (num >= romanMatrix[i][0]) { return romanMatrix[i][1] + convertToRoman(num - romanMatrix[i][0]); } } }

Number.fromRoman = function (roman, accept) { var s = roman.toUpperCase().replace(/ +/g, ''), L = s.length, sum = 0, i = 0, next, val, R = { M: 1000, D: 500, C: 100, L: 50, X: 10, V: 5, I: 1 };

function fromBigRoman(rn) { var n = 0, x, n1, S, rx =/(\(*)([MDCLXVI]+)/g;

while ((S = rx.exec(rn)) != null) { x = S[1].length; n1 = Number.fromRoman(S[2]) if (isNaN(n1)) return NaN; if (x) n1 *= Math.pow(1000, x); n += n1; } return n; }

if (/^[MDCLXVI)(]+$/.test(s)) { if (s.indexOf('(') == 0) return fromBigRoman(s);

while (i < L) { val = R[s.charAt(i++)]; next = R[s.charAt(i)] || 0; if (next - val > 0) val *= -1; sum += val; } if (accept || sum.toRoman() === s) return sum; } return NaN; };

function convert(num) { if(num < 1){ return "";} if(num >= 40){ return "XL" + convert(num - 40);} if(num >= 10){ return "X" + convert(num - 10);} if(num >= 9){ return "IX" + convert(num - 9);} if(num >= 5){ return "V" + convert(num - 5);} if(num >= 4){ return "IV" + convert(num - 4);} if(num >= 1){ return "I" + convert(num - 1);} } console.log(convert(39)); //Output: XXXIX This will only support numbers 1-40, but it can easily be extended by following the pattern.

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/9083037/convert-a-number-into-a-roman-numeral-in-javascript https://www.w3resource.com/javascript-exercises/javascript-math-exercise-21.php

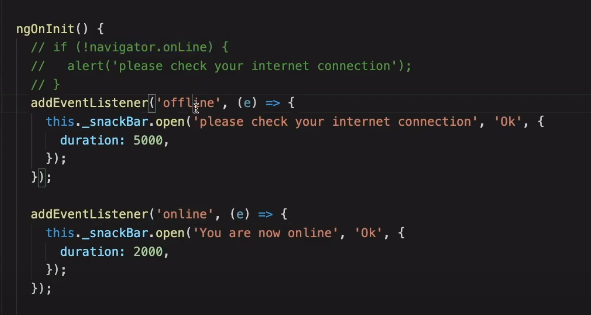

How to check User online or offline status

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yqNgZDIgIeM

|

|

|

|

|

|

console.log(Array.from({ length: 10 }, (v, k) => k + 1))

// http://dmitripavlutin.com/javascript-array-from-applications/

const someNumbers = { '0': 10, '1': 15, length: 2 }

Array.from(someNumbers, value => value * 2) // => [20, 30]

const length = 3 const init = 0 const result = Array.from({ length }, () => init)

result // => [0, 0, 0]

const length = 3 const init = 0 const result = Array(length).fill(init)

fillArray2(0, 3) // => [0, 0, 0]

|

https://medium.com/@tdillusionisme/javascript-iife-and-why-to-use-them-cbdff335f565

|

IIFE

IIFE stands for ‘Immediately Invoked Function Expression’ Self-Executing Anonymous Function

Reduces the global variable namespace pollution and improves performance. See the difference below

<script> var glob_a = 10; setTimeout(() => console.log(glob_a),1000); //30 </script> <script> var glob_a = 20; setTimeout(() => console.log(glob_a),1000); //30 </script> <script> var glob_a = 30; setTimeout(() => console.log(glob_a),1000); //30 </script>

<script> (function(){ var glob_a = 10; setTimeout(() => console.log(glob_a),1000); //10 })(); </script> <script> (function(){ var glob_a = 20; setTimeout(() => console.log(glob_a),1000); //20 })(); </script> <script> (function(){ var glob_a = 30; setTimeout(() => console.log(glob_a),1000); //30 })(); </script>

Hide 🙈 all console logs in production with just 3 lines of code

if (env === 'production') { console.log = function () {}; }

if (env === 'production') { const noop = () => {} ['assert', 'clear', 'count', 'debug', 'dir', 'dirxml', 'error', 'exception', 'group', 'groupCollapsed', 'groupEnd', 'info', 'log', 'markTimeline', 'profile', 'profileEnd', 'table', 'time', 'timeEnd', 'timeline', 'timelineEnd', 'timeStamp', 'trace', 'warn', ].forEach((method) => { window.console[method] = noop }) }

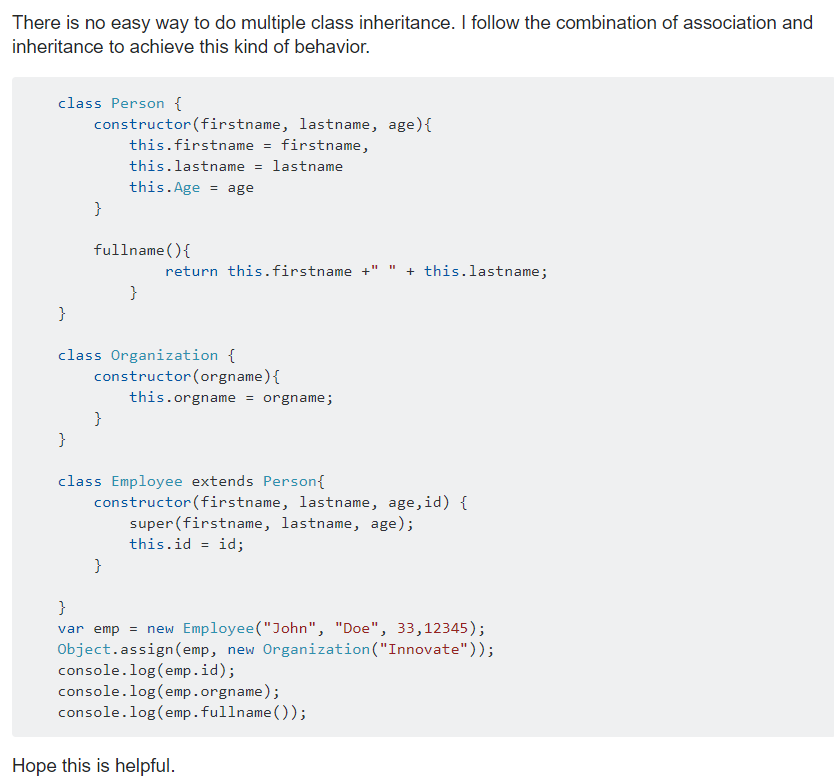

ES6 Class Multiple inheritance

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/29879267/es6-class-multiple-inheritance/45332959

// base class class A { foo() { console.log(`from A -> inside instance of A: ${this instanceof A}`); } }

// B mixin, will need a wrapper over it to be used const B = (B) => class extends B { foo() { if (super.foo) super.foo(); // mixins don't know who is super, guard against not having the method console.log(`from B -> inside instance of B: ${this instanceof B}`); } };

// C mixin, will need a wrapper over it to be used const C = (C) => class extends C { foo() { if (super.foo) super.foo(); // mixins don't know who is super, guard against not having the method console.log(`from C -> inside instance of C: ${this instanceof C}`); } };

// D class, extends A, B and C, preserving composition and super method class D extends C(B(A)) { foo() { super.foo(); console.log(`from D -> inside instance of D: ${this instanceof D}`); } }

// E class, extends A and C class E extends C(A) { foo() { super.foo(); console.log(`from E -> inside instance of E: ${this instanceof E}`); } }

// F class, extends B only class F extends B(Object) { foo() { super.foo(); console.log(`from F -> inside instance of F: ${this instanceof F}`); } }

// G class, C wrap to be used with new decorator, pretty format class G extends C(Object) {}

|

|||

|

class Nose { constructor() { this.booger = 'ready'; }

pick() { console.log('pick your nose') } }

class Ear { constructor() { this.wax = 'ready'; }

dig() { console.log('dig in your ear') } }

class Gross extends Classes([Nose,Ear]) { constructor() { super(); this.gross = true; } }

function Classes(bases) { class Bases { constructor() { bases.forEach(base => Object.assign(this, new base())); } } bases.forEach(base => { base.prototype .properties() .filter(prop => prop != 'constructor') .forEach(prop => Bases.prototype[prop] = base.prototype[prop]) }) return Bases; }

// test it function dontLook() { var grossMan = new Gross(); grossMan.pick(); // eww grossMan.dig(); // yuck! }

Well Object.assign gives you the possibility to do something close albeit a bit more like composition with ES6 classes.

class Animal { constructor(){ Object.assign(this, new Shark()) Object.assign(this, new Clock()) } }

class Shark { // only what's in constructor will be on the object, ence the weird this.bite = this.bite. constructor(){ this.color = "black"; this.bite = this.bite } bite(){ console.log("bite") } eat(){ console.log('eat') } }

class Clock{ constructor(){ this.tick = this.tick; } tick(){ console.log("tick"); } }

let animal = new Animal(); animal.bite(); console.log(animal.color); animal.tick();

I've not seen this used anywhere but it's actually quite useful. You can use function shark(){} instead of class but there are advantages of using class instead. I believe the only thing different with inheritance with extend keyword is that the function don't live only on the prototype but also the object itself. Thus now when you do new Shark() the shark created has a bite method, while only its prototype has a eat method

https://github.com/latitov/OOP_MI_Ct_oPlus_in_JS

|

|||

|

class Car { constructor(brand) { this.carname = brand; } show() { return 'I have a ' + this.carname; } }

class Asset { constructor(price) { this.price = price; } show() { return 'its estimated price is ' + this.price; } }

class Model_i1 { // extends Car // and Asset (just a comment for ourselves) // constructor(brand, price, usefulness) { specialize_with(this, new Car(brand)); specialize_with(this, new Asset(price)); this.usefulness = usefulness; } show() { return Car.prototype.show.call(this) + ", " + Asset.prototype.show.call(this) + ", Model_i1"; } }

function specialize_with(o, S) { for (var prop in S) { o[prop] = S[prop]; } }

mycar = new Model_i1("Ford Mustang", "$100K", 16);

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

https://aparnajoshi.netlify.app/object-oriented-programming-with-javascript

function Vehicle(name, cost, engineType) { this.name = name || ''; this.cost = cost || 0; this.engineType = engineType || 'petrol';

}

Vehicle.prototype = { constructor: Vehicle, getEngineType: function () { return this.engineType; }, calculateEmi: function () { return this.cost * 0.12; }, setEngineType: function (type) { this.engineType = type; } }

var vehicle1 = new Vehicle('Lamborghini Gallardo', 20000, 'petrol'); console.log(vehicle1.getEngineType()); // petrol vehicle1.setEngineType('diesel'); console.log(vehicle1.getEngineType()); // diesel

function Car(model, hasFuel, color, name, cost, engineType ) { this.model = model || ''; this.hasFuel = hasFuel || false; this.color = color || ''; this.name = name || ''; this.cost = cost || 0; this.engineType = engineType || 'petrol'; }

OR

function Car(model, hasFuel, color, name, cost, engineType ) { this.model = model || ''; this.hasFuel = hasFuel || false; this.color = color || ''; Vehicle.call(this, [name, cost, engineType]); }

Car.prototype = new Vehicle(); // Car.prototype = Object.create( Vehicle.prototype ); // This works too Car.prototype.constructor = Car;

var lambo = new Car('gallardo', true, 'yellow', 'Lamborighini', 20000, 'petrol'); console.log(lambo.calculateEmi()); // 2400

Class-based inheritance and encapsulation: ES6

class Vehicle { constructor(name, cost, engineType){ this.name = name || ''; this.cost = cost || 0; this.engineType = engineType || 'petrol'; }

getEngineType() { return this.engineType; }

calculateEmi() { return this.cost * 0.12; }

setEngineType(type) { this.engineType = type; } }

class Car extends Vehicle{ constructor(model, hasFuel, color, name, cost, engineType) { super(name, cost, engineType); this.model = model || ''; this.hasFuel = hasFuel || false; this.color = color || ''; } }

var lambo = new Car('gallardo', true, 'yellow', 'Lamborighini', 20000, 'petrol'); console.log(lambo.calculateEmi()); // 2400

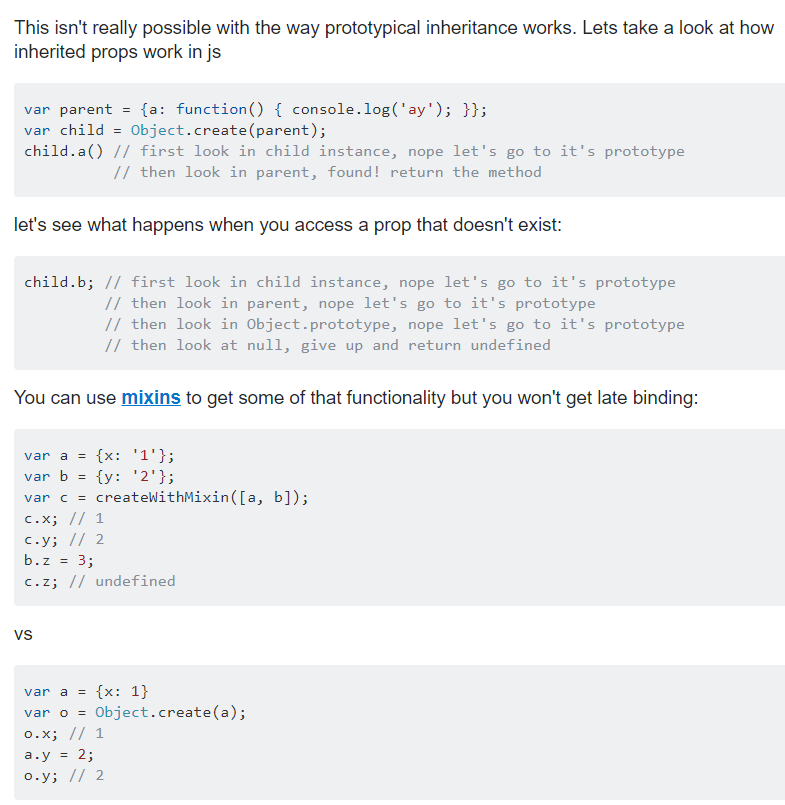

prototypes have its drawbacks. Any change in one of the properties will be reflected in all the objects.

function Apple(name, color) { this.name = name; this.color = color }

Apple.prototype.value = 20;

var apple1 = new Apple("Apple", "Red"); var apple2 = new Apple("Apple2", "Wheatish Red");

console.log(apple1.name); // Apple console.log(apple1.value); // 20 console.log(apple2.value); // 20

Apple.prototype.value = 40; console.log(apple1.value); // 40 console.log(apple2.value); // 40

apple1.value = 30; console.log(apple1.value); // 30 console.log(apple2.value); // 40

The context of this can be changed

var person1 = { firstName: "Jensen", lastName: "Ackles", showFullName: function () { console.log(this.firstName + " " + this.lastName); } }

var person2 = { firstName: "Dean", lastName: "Winchester", }

person1.showFullName (); // Jensen Ackles - this refers to person1 object person1.showFullName.apply(person2); // Dean Winchester - this refers to person2 object

forced the context of this to person2 this when borrowing methods:

var person1 = { firstName: "Jensen", lastName: "Ackles", showFullName: function () { return this.firstName + " " + this.lastName; } }

var person2 = { firstName: "Dean", lastName: "Winchester", }

person2.fullName = person1.showFullName(); console.log(person2.fullName); // Jensen Ackles - this refers to person1 object person2.fullName = person1.showFullName.apply(person2); console.log(person2.fullName); // Dean Winchester - this refers to person2 object

var person = { firstName: "Jensen", lastName: "Ackles", fullName: function () { return this.firstName + " " + this.lastName; } }

var showFullName = person.fullName; console.log(showFullName()); // undefined undefined

its context is not set to the global variable. Since the global window object doesn't contain the value of firstName and lastName, they are printed as undefined. To fix this problem, we can set the value of this to a particular object indefinitely using bind:

var person = { firstName: "Jensen", lastName: "Ackles", fullName: function () { return this.firstName + " " + this.lastName; } }

var showFullName = person.fullName.bind(person); console.log(showFullName()); // Jensen Ackles

this when used inside a method as a callback:

var person = { firstName: "Jensen", lastName: "Ackles", fullName: function () { console.log(this.firstName + " " + this.lastName); } }

setTimeout(person.fullName, 1000); // undefined undefined

The above code works similarly to how the context of this changes when it is assigned to a variable. One can assume that the setTimeOut function has a variable that takes the function as a parameter, and then it executes on the global object. Since the global object doesn't contain the definition to firstName and lastName, the value is printed as undefined. To fix this, we need to bind the value of this to the object on which it should be applied. This is a pattern most commonly seen when we are defining callback functions to the javascript events.

setTimeout(person.fullName.bind(person), 1000); // Jensen Ackles

this when used inside a closure:

Another instance when the value of this is misunderstood is when this is used inside closures.

var person = { fullName: "Jensen Ackles", getDetails: function () { var closureFunction = function() { console.log(this.fullName); // undefined console.log(this); // global window object } closureFunction(); } }

person.getDetails();

The value of this doesn't refer to the person object, rather it refers to the global window object. We have two ways of mitigating this problem:

1. Assign the value of this to an explicit variable, and then use that variable to access the properties.

var person = { fullName: "Jensen Ackles", getDetails: function () { var personObj = this; var closureFunction = function() { console.log(personObj.fullName); // Jensen Ackles console.log(personObj); // person Object } closureFunction(); } }

person.getDetails();

2. Use arrow function provided by **ES6: Arrow function preserves the context of this.**

var person = { fullName: "Jensen Ackles", getDetails: function () { var closureFunction = () => { console.log(this.fullName); // Jensen Ackles console.log(this); // person Object } closureFunction(); } }

person.getDetails();

This article has aimed at providing a detailed understanding of how this is used in javascript and has warned about the pitfalls which can be avoided while using this. Using javascript's apply, call, bind and arrow functions, we can control the value of this to meet our needs. As a final note, please remember that the value of this is usually the object on which the function is called.

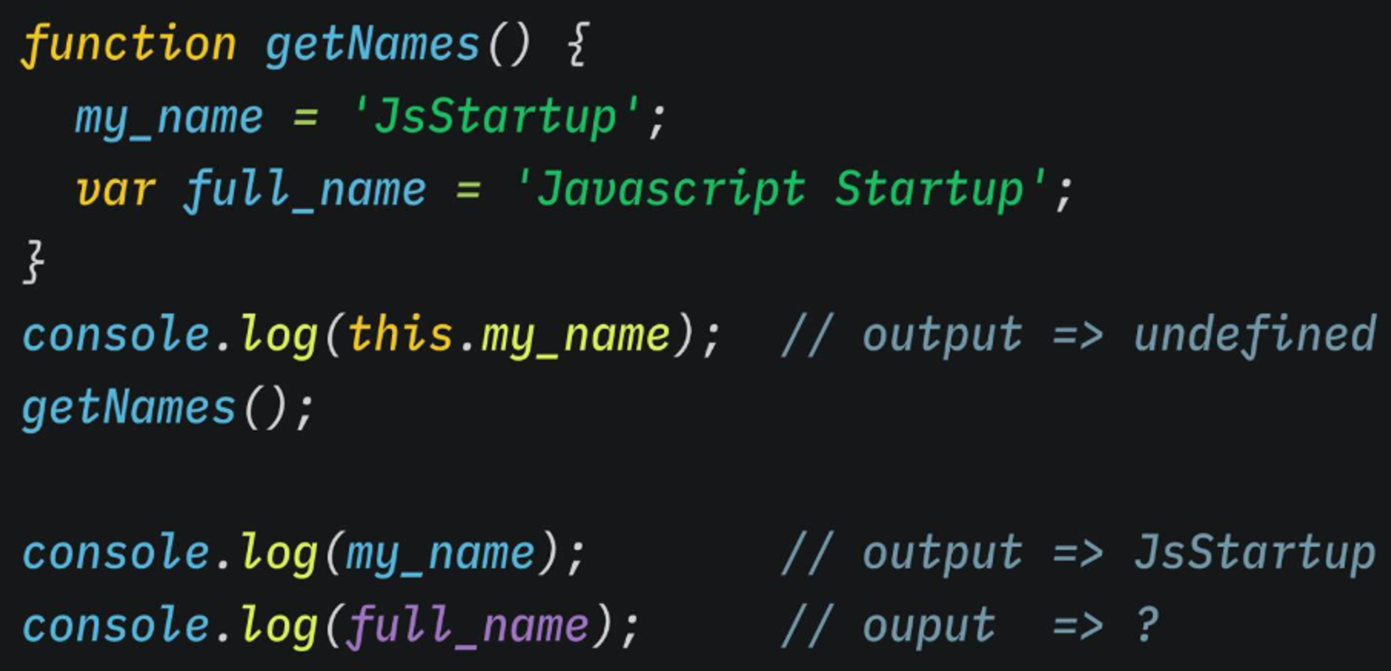

"ReferenceError: full_name is not defined

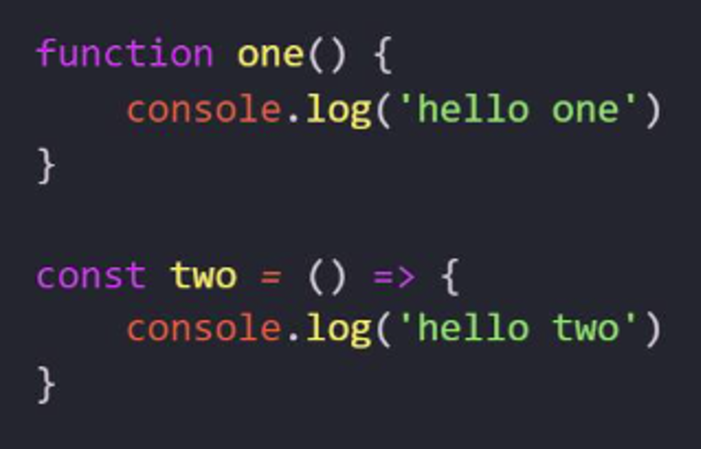

What are the differences/advantages between these functions?

Arrow function dosent have its own this, it consider parents this. The first one is initialized and hoisted immediately the first time js engine goes through the code. The second one is not hoisted and not initialised already at the beginning. Therefor you can write the first one at any place, but the second one you need to position in your code before it is called. Also the second one always hase lexical scope. So the this keyword will not return the object on which the function is called but refers to the nearest scope. If we use arrow function then we don't have to explicitly bind the function.

var mathLib = { pi: 3.14, area: function(r) { return this.pi * r * r; }, circumference: function(r) { return 2 * this.pi * r; } };

mathLib.area(2); // 12.56

mathLib.area.call({pi: 3.14159}, 2); // takes new pi value on the ply // that is the beauty of call

var cylinder = { pi: 3.14, volume: function(r, h) { return this.pi * r * r * h; } };

cylinder.volume.call({pi: 3.14159}, 2, 6); 75.39815999999999

cylinder.volume.apply({pi: 3.14159}, [2, 6]); 75.39815999999999

What is the use of Bind? It allows us to inject a context into a function which returns a new function with updated context. It means this variable will be user supplied variable. This is very useful while working with JavaScript events.

• Global scope • Local Scope/Function scope • Block scope(Introduced in ES6)

pi = 3.14; function circumference(radius) { pi = 3.14159; console.log(2 * pi * radius); // Prints "12.56636" not "12.56" }circumference(2);

var a = 10;

function Foo() { if (true) { let a = 4; }

alert(a); // alerts '10' because the 'let' keyword }Foo();

Closure

JavaScript closure is a function that returns another function.

Write a design that takes a string and returns a character at a time. If the new string is given, it should replace the old one. It is simply called a generator.

function generator(input) { var index = 0; return { next: function() { if (index < input.length) { index += 1; return input[index - 1]; } return ""; } } }

var mygenerator = generator("boomerang"); mygenerator.next(); // returns "b" mygenerator.next() // returns "o"mygenerator = generator("toon"); mygenerator.next(); // returns "t"

function Foo(){ console.log(this.a); }

var food = {a: "Magical this"};

Foo.call(food); // food is this

Object.seal is slightly different from the freeze. It allows configurable properties but won’t allow new property addition or deletion or properties.

var marks = {physics: 98, maths:95, chemistry: 91}; Object.seal(marks); delete marks.chemistry; // returns false as operation failed marks.physics = 95; // Works! marks.greek = 86; // Will not add a new property

Object.freeze allows us to freeze an object so that existing properties cannot be modified.

var marks = {physics: 98, maths:95, chemistry: 91}; finalizedMarks = Object.freeze(marks); finalizedMarks["physics"] = 86; // throws error in strict mode console.log(marks); // {physics: 98, maths: 95, chemistry: 91}

Understand the callbacks and promises well

regex

var re = /ar/; var re = new RegExp('ar'); // This too works re.exec("car"); // returns ["ar", index: 1, input: "car"] re.exec("cab"); // returns

/* Character class */ var re1 = /[AEIOU]/; re1.exec("Oval"); // returns ["O", index: 0, input: "Oval"] re1.exec("2456"); // var re2 = /[1-9]/; re2.exec('mp4'); // returns ["4", index: 2, input: "mp4"]/* Characters */var re4 = /\d\D\w/; re4.exec('1232W2sdf'); // returns ["2W2", index: 3, input: "1232W2sdf"] re4.exec('W3q'); // returns /* Boundaries */ var re5 = /^\d\D\w/; re5.exec('2W34'); // returns ["2W3", index: 0, input: "2W34"] re5.exec('W34567'); // returns var re6 = /^[0-9]{5}-[0-9]{5}-[0-9]{5}$/; re6.exec('23451-45242-99078'); // returns ["23451-45242-99078", index: 0, input: "23451-45242-99078"] re6.exec('23451-abcd-efgh-ijkl'); // returns /* Quantifiers */ var re7 = /\d+\D+$/; re7.exec('2abcd'); // returns ["2abcd", index: 0, input: "2abcd"] re7.exec('23'); // returns

re7.exec('2abcd3'); // returns var re8 = /<([\w]+).*>(.*?)<\/\1>/; re8.exec('<p>Hello JS developer</p>'); //returns "<p>Hello JS developer</p>"

Understand Error handling patterns

$("button").click(function(){ $.ajax({url: "user.json", success: function(result){ updateUI(result["posts"]); }}); });

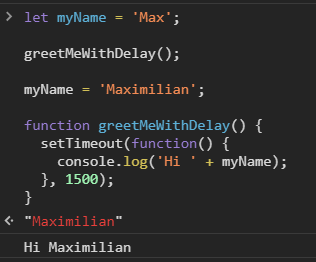

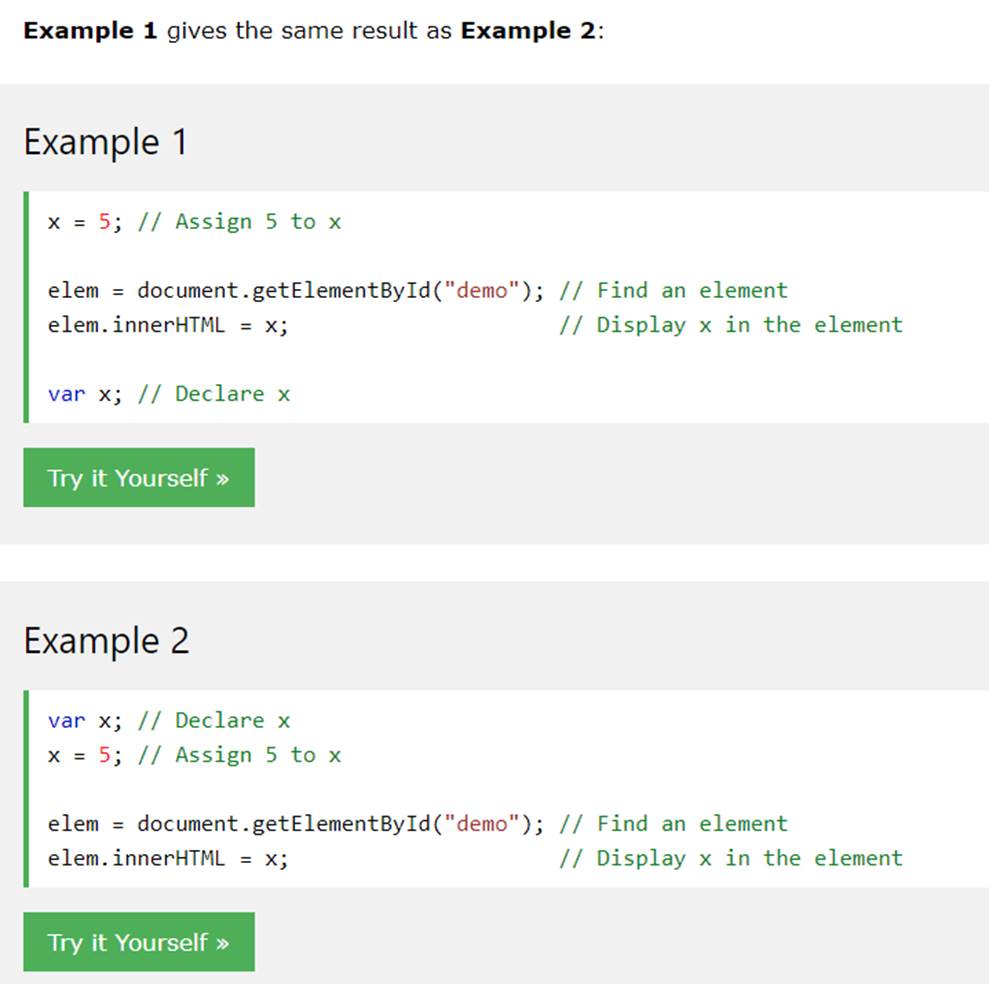

Hoisting Hoisting is a process of pushing the declared variables to the top of the program while running it.

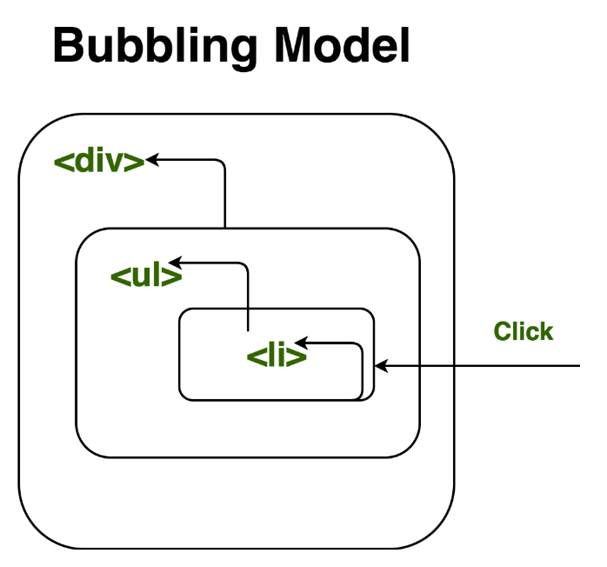

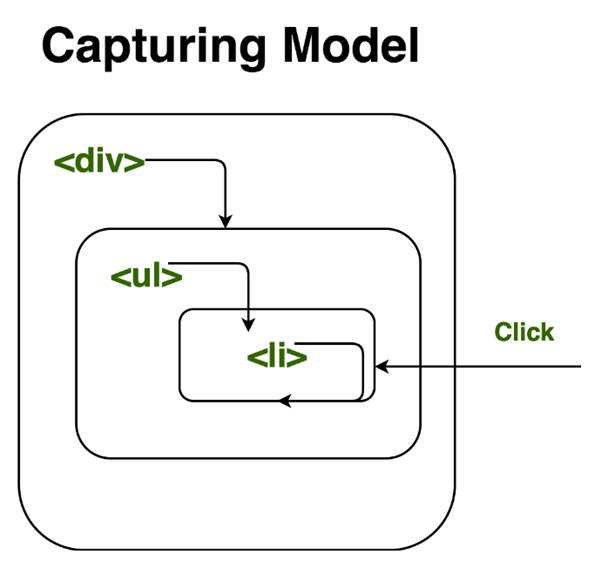

Event Bubbling

Event bubbling and capturing are two ways of event propagation in the HTML DOM API when an event occurs in an element inside another element, and both elements have registered a handler for that event. The event propagation mode determines in which order the elements receive the event.”

With bubbling, the event is first captured and handled by the innermost element and then propagated to outer elements. With capturing, the process is in reverse. We usually attach an event to a handler using the addEventListener function.

addEventListener("click", handler, useCapture=false)

The third argument useCapture is the key. The default value is false. So, it will be a bubbling model where the event is handled by the innermost element first and it propagates outwards till it reaches the parent element. If that argument is true, it is capturing model.

When You Should Use JavaScript Maps over Objects

These limitations are solved by maps. Moreover, maps provide benefits like being iterators and allowing easy size look-up.Objects are not good for information that’s continually updated, looped over, altered, or sorted.

Use objects the vast majority of the time, but if your app needs one of these extra bits of functionality, use map.

What’s a “Closure”? Every function in JavaScript is a closure! That means that every function closes over its environment when it’s created.

because the value is only looked up when its needed, not when the closure is created!

Now let's define a closure: A closure is the combination of a function bundled together (enclosed) with references to its surrounding state (the lexical environment)

JavaScript Hoisting

|

|||